Often referred to as the “mother gland,” the pituitary gland is a tiny yet mighty organ that plays a crucial role in how we respond to stress – both physically and emotionally. Understanding its function not only demystifies the biochemical dance of our stress responses but also empowers us to manage stress more effectively in our daily lives.

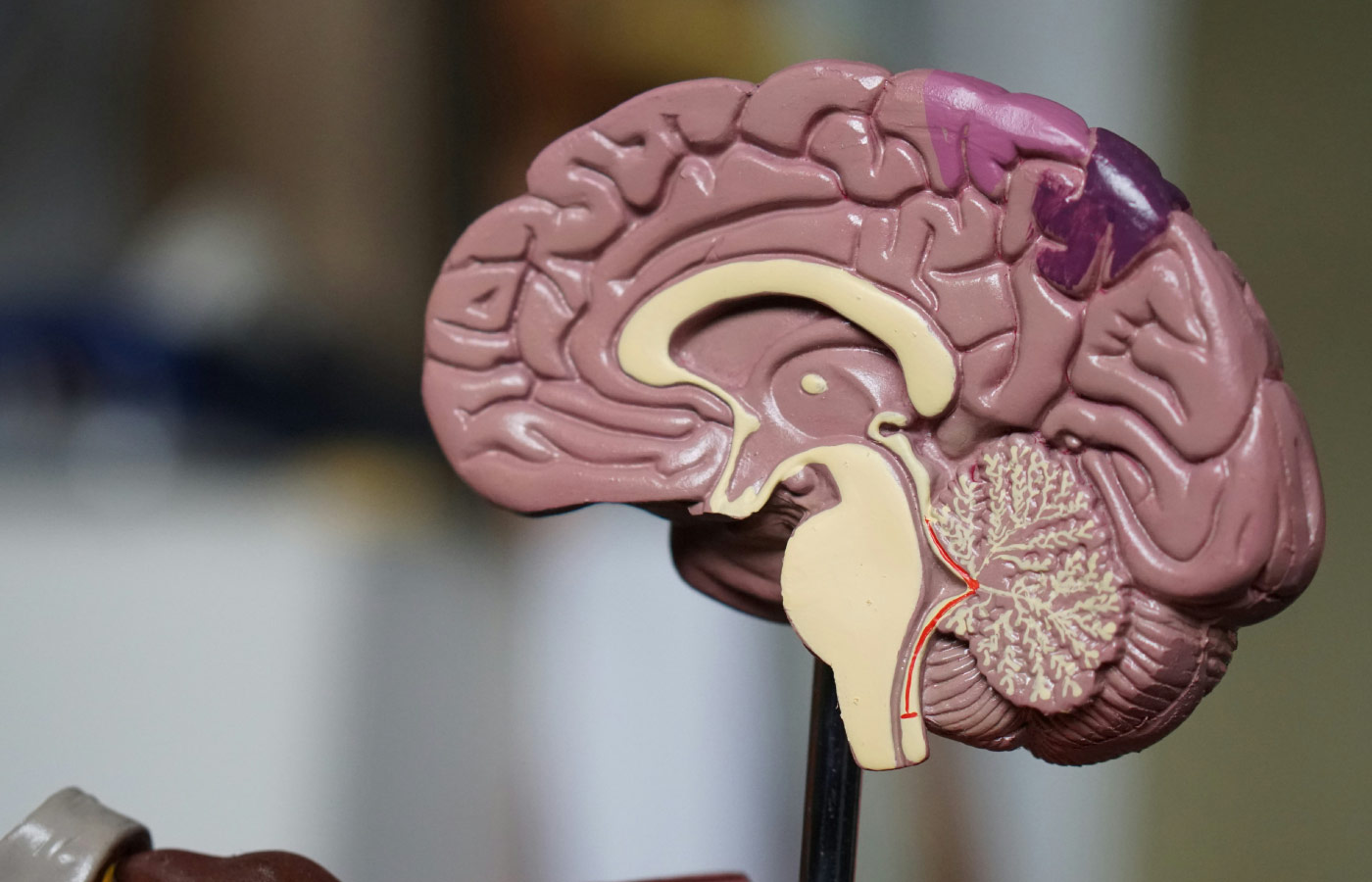

Imagine a typical day: you’re late for a meeting, your phone is ringing off the hook, and you just received an email that has upset you. Internally, a less visible scenario unfolds: your brain’s hypothalamus, constantly scanning the environment inside and outside your body, senses your distress and queries, “Am I safe?” When the answer is a resounding “no,” (which it is when adrenaline escalates when you’re starting to feel anxious, pressured or on edge, regardless of whether you’re physically in danger or have just consumed too much caffeine) it quickly sends a signal to the pituitary gland, which decides the next steps in this stress dance.

This pea-sized gland, nestled securely at the base of your brain, springs into action. It communicates the ‘danger’ to other glands, signalling the adrenal glands atop your kidneys to release cortisol and adrenaline, preparing your body to either confront the challenge head-on or to make a swift exit – the classic “fight or flight” response.

This cascade, known collectively as the HPA axis, involves not only the hypothalamus and pituitary gland but also the adrenal glands. It’s a finely tuned system designed for short-term emergencies. However, in our modern lives, where stressors such as traffic jams or work deadlines are commonly continuous, this system can be in perpetual motion. This ongoing activation can have profound implications, wearing down our body and mind, much like an orchestra playing a relentless fortissimo without a break.

The hypothalamus also works in concert with the nervous system – in this scenario, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) – which can amplify the stress response even further. When the SNS is engaged, it enhances the production of noradrenaline, akin to adding more instruments to an already loud musical section, increasing the volume of the body’s stress response.

The personal cost of a perpetual crescendo

Living in this high-stress mode can lead to a range of health issues – imagine the wear on the musicians in an orchestra playing without pause. From anxiety and depressed mood, to heart disease and weakened immune function, the costs are high. It’s akin to an orchestra out of sync, where the harmony is disrupted, leading to a performance that is grating or lack lustre.

To mitigate the effects of stress, consider these strategies:

Mindful practices: Engage in mindfulness, meditation, or yoga to reduce the hypothalamic perception of threat, thereby lessening the pituitary gland’s need to initiate a stress response. This article can help if you find it hard to fit mindfulness into your busy schedule.

Nutritional support: Foods rich in vitamin C, magnesium, and omega-3 fatty acids can support adrenal health while zinc is essential for hormone production.

Adequate rest: Ensuring sufficient sleep helps recalibrate the body’s stress hormone systems, allowing for a more adaptive response.

Regular movement: Physical activity can help to modulate the SNS activity and increase the resilience of your stress response systems.

Understanding the role of the pituitary gland in the stress response doesn’t just add a chapter to our biological textbooks; it opens up avenues for proactive health management. By recognising the signals that trigger our stress responses and adjusting our lifestyle to support our endocrine health, we can protect ourselves from the ravages of chronic stress. This knowledge empowers us to not just survive but thrive, even in the face of daily challenges.